Giuseppe Pastacaldi, an Italian in Africa between the 1800 and 1900s.

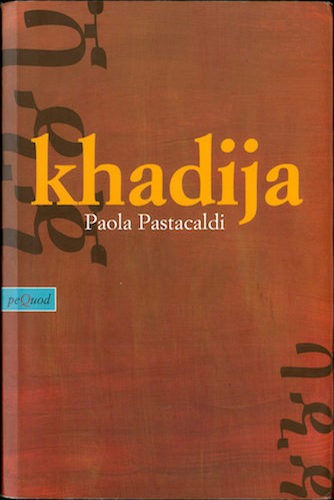

Europeans have always shown a great deal of interest in Ethiopia. On the request of the English government, the explorer Richard Burton organized an expedition to Eastern Ethiopia in 1854 in search of its treasures. He was the first European to enter the ancient, sacred city of Harar and remain there ten days, risking his life dressed as an Arab. Burton wrote a book recalling this experience, First Footsteps in East Africa (Primi passi nell’Africa orientale). In those days Ethiopia was called Abyssinia descending from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Italian colonization, in that which would later be called Italian East Africa, began in 1882, when the port of Assab, on the southern shores of the Red Sea, was sold by a sultan to a Genoese seagoing company, Rubattino. Assab became the base for the first Italian colony in Eritrea. However, attempted expansion inland led to a conflict with the Ethiopian Empire at that time under the Emperor Menelik. In 1889, the Kingdom of Italy signed the controversial treaty of Uccialli with Ethiopia. This treaty was to regulate relations between the two states and acknowledge the recent territorial gains made by Italy in Eritrea which was to be recognized as a colony and stated that Italy would be in charge of handling all foreign policy. In 1896, the Italians were badly defeated by the Ethiopians at Adua. Many soldiers were castrated or made slaves. In these difficult times only men of great courage travelled inland into Abyssinia to explore places never seen before. Among these there are Vittorio Bottego, Luigi Robecchi Bricchetti, Carlo Piaggia, Giuseppe Maria Giulietti, Orazio Antinori, Antonio Cecchi, Miani and many others who paid with their lives, ending up slaughtered or dying in pain and solitude. Many European governments longed to receive information regarding this part of Africa, particularly from the British and French. Obviously, the Italians were a kind of taillight who tagged on to the British. One of the most strategic places from whence to keep an eye on Menelik and his men was Harar, the walled holy city which had been Muslim for centuries and inhabited by Hyenas and ferocious animals. Harar was the destination of explorers, traders and diplomats and for this reason was called the Rome of Africa. The writer Edoardo Scarfoglio (who was married to Matilde Serrao), wrote a four-page supplement in December 1891 for the newspaper ‘Corriera della Sera’, entitled ‘Journey to Harar’, which was included with the paper and given to subscribers. The French poet Rembaud spent the last years of his life there, reading the Koran and living with the natives. He left an extremely interesting diary recounting his experience. The road to Harar was on the old slave route and, therefore, very dangerous. In 1890, Count Porro was sent to Harar with a caravan all financed by the Commercial Exploration Society of Milan with the intention of opening up a route for Italian invasion. However, he was slaughtered with all his men and the natives travelling in the party during an ambush organized by the Pasha of Egypt who was then governor of Harar. At the end of the 1800s my grandfather, Giuseppe Pastacaldi (Livorno 1871 – Harar 1921), came ashore in Harar from Aden certainly having sailed in a sambuk, an ancient boat with a latin sail. He had fled Livorno following a duel. In those days young Italian men would fight duels for the most futile reasons, copying the fashion in vogue among young German university students. They thought that having a scar resulting from a duel was a sign of courage and honour. And so it was that Giuseppe Pastacaldi, a young student from Pisa, maybe wanting to show off his prowess to a lady, challenged a fellow student to a duel – and killed him. Obliged to flee in order to avoid prison, he took a ship in Livorno bound for Aden, where his sister lived, married to the Vice-consul. A short time later he left Yemen sailing towards the African coast and the city of Harar, on the border with Somalia, where he lived until he died in 1921.During his lifetime he worked for the Italian government maintaining contact with ‘ras’ (boss) Makonnen and Melenik and supplying information on the movements of the local governors, the ras. Giuseppe Pastacaldi was correspondent for the Italian Colonial Society of Aden in the Harar agency and in 1898 founded the Mombassa branch since he was director of logistics for the house of Bienenfeld on behalf of the British government, in charge of the whole area between Mombassa and Lake Victoria. He worked in the Colonial Society headquarters in Uganda and then in Cassala, and for Bienenfeld was also their agent in Addis Abeba. He certainly played a very important diplomatic role in the future Horn of Africa thanks to his good knowledge of the territory and the many contacts he had in the local authorities. He died in 1921 and was buried in the Catholic cemetery in Harar. He lived with (but never married as was the custom in those days) a native Galla woman who was a muslim converted to Christianity, whose name was Khadija and with whom he had seven children, all educated in the catholic galla mission under the direction of the vicar apostolic André Jarousseau. All seven children spoke fluent Galla, Somali, Amhara, French, Italian as well as Arabic. Upon the death of their father they all moved to Asmara with their mother to attend the only school in Ethiopia for mixed-breeds. I am the granddaughter of Giuseppe’s youngest son, Leone Pastacaldi. In 2005 I published a historial novel telling the story of the events relating to the lives of my grandmother and my grandfather Giuseppe. With this novel, whose title is the name of my grandmother Khadija (peQuod, 2005) I won the Vigevano prize. Giuseppe Pastacaldi’s diplomatic carreer as consular agent in Harar was discussed in length by Governor Ferdinando Martini ( who later became minister of the colonies) and by General Ciccodicola. However, as can be seen in the documents in the possession of the Farnesina (the Foreign Ministry), he was fired as the result of a deal regarding the purchase of camels which went wrong. The Anglo-Egyptians had asked him to buy a large number of camels. Giuseppe Pastacaldi made a substantial order and once the camels had reached the Arabian coast and were ready to be shipped to Cassala, the Anglo-Egyptians changed their minds, causing the Italian Colonial Society to lose seventy- thousand lire. Notwithstanding his ‘undisputed morality which was recognized by everyone’, Giuseppe Pastacaldi was considered the person responsible for this commercial debacle and, as a consequence, his consular position in Harar was not renewed. You can read a dossier about Giuseppe Pastacaldi in the diplomatic archives of the Farnesina (The Foreign Ministry) and his name is also mentioned in a number of texts written during the period, as well as in the diary of General Alberto Pollera, one of the most important men in the fascist government of Italian East Africa. (See: E.A. Albertis, Una Gita a Harar (A Trip to Harar), Fratelli Treves Editori, Milan, 1906; Martini F., Nell’Africa Italiana, impressioni e ricordi 1895 ( In Italian Africa, impressions and memories 1895), Fratelli Treves, Milan, 1925; Bollettino Società Africana d’Italia Dall’Harar Missione per la delimitazione del confine tra Somalia Italiana e l’Etiopia 1910 (Bulletin of the African Society of Italy from the Harar Mission to mark the boundary between Italian Somalia and Ethiopia, 1910)